PRP injections for knee osteoarthritis

What is PRP?

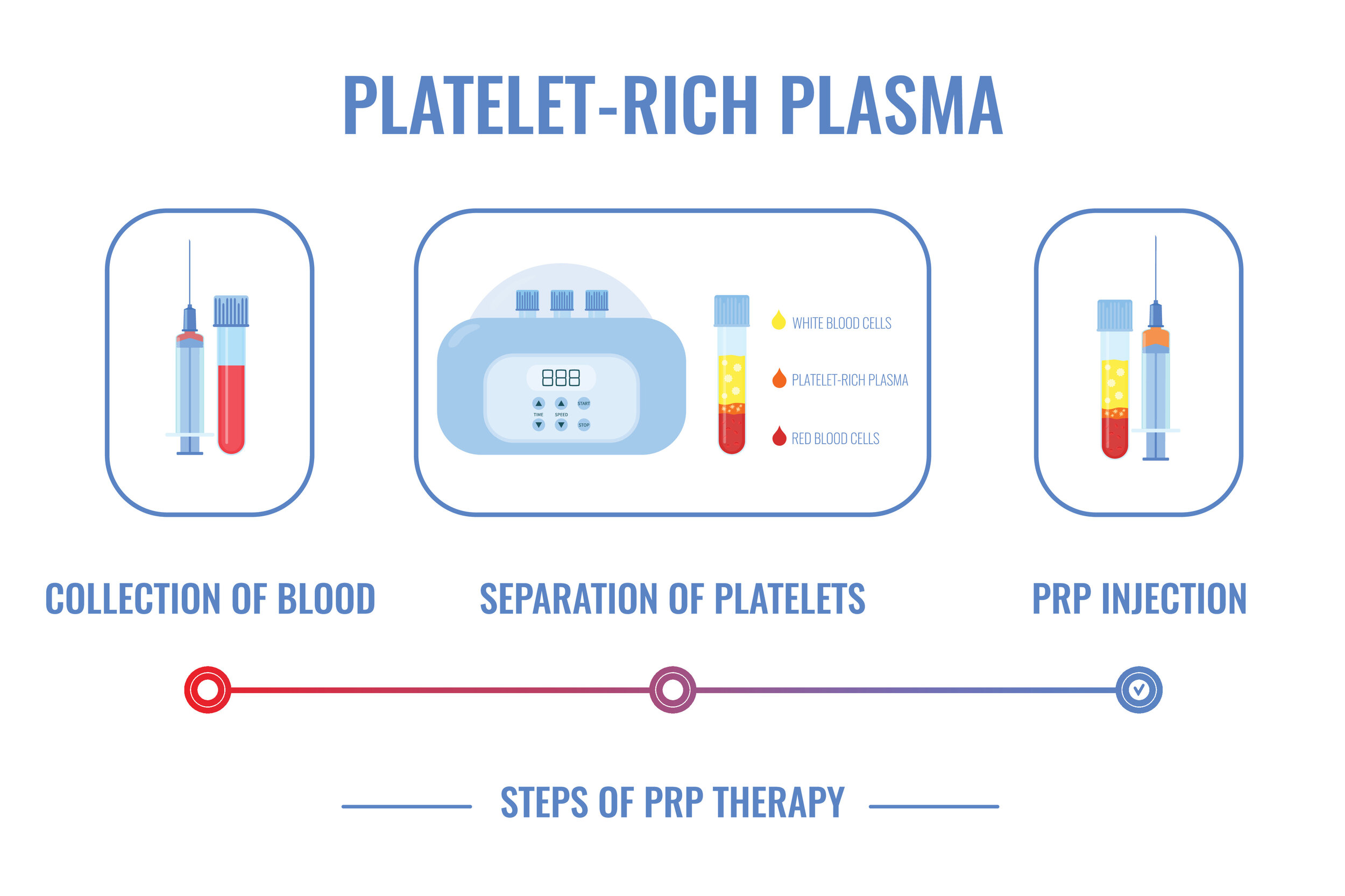

PRP stands for platelet rich plasma. Blood is made from 3 main components: blood cells (red & white), platelets and plasma (liquid component). PRP is a concentrated form of platelets that contains healing factors.

What is PRP used for?

PRP can be used to help with the symptoms of knee osteoarthritis. It is also used to help with chronic tendon injuries e.g. patella tendinopathy.

How does PRP work?

PRP is rich in growth factors which have been shown to promote stem cell recruitment, cause the formation of new blood vessels and reduce inflammation. It also may have a regenerative effect and can stimulate the production of cartilage cells.

What are the different methods of preparing PRP?

There are numerous methods of preparing PRP.

Preparation involves 4 fundamental steps:

- Blood draw

- Centrifugation

- Activation

- Administration

-

30-60mL of blood is taken from the patient.

-

The blood is spun in a centrifugation machine which separates the blood components (red blood cells, white blood cells, platelets and plasma) by weight. The heavier components will settle beneath the lighter components.

-

Activation is a crucial step of the process. Chemicals are added into the PRP to cause the platelets to release the stored growth factors (within the platelets) into the external environment.

-

The PRP is injected into the knee joint.

The way PRP is prepared can vary between different clinicians and labs. The spin time, spin rate and activation method can all differ and therefore result in a differing amount of growth factor release even though the fundamental steps remain the same.

How long does PRP last in knee?

If PRP is used for early osteoarthritis, most patients can expect to feel symptomatic relief for up to 6-12 months.

How many PRP injections are needed for knee osteoarthritis?

In the setting of knee osteoarthritis, a single injection of PRP within the knee is unlikely to produce lasting results. The optimal modality is three injections spaced 2 weeks apart. A recently published study has shown that 3 injections of PRP (blue bar) lead to larger improvements in pain and function than 1 injection of PRP (orange bar) [1].

Can PRP regenerate cartilage?

Lab studies have shown that PRP can modulate the repair and regeneration of repaired cartilage within the joint. It causes stem cells to migrate to the area of damage where they can proliferate (increase in number) and differentiate (change into cartilage cells).

PRP also works by decreasing the inflammation within the lining of the knee joint (synovium) where the pain receptors are located.

PRP does not transform a frankly arthritic knee joint back to normal.

Does PRP actually work for knee osteoarthritis?

In early or mid-stage osteoarthritis of the knee, the results of 14 randomized control trials (the best methodological quality of a research trial) showed that PRP significantly improved pain and function compared to other types of injections (steroids, hyaluronic acid and normal saline) [2].

How does PRP compare to viscosupplementation of the knee?

Viscosupplementation involves injecting synthetic hyaluronic acid into the knee. Hyaluronic acid is normally produced by the cells lining the knee joint (synovium) and acts as a lubricant within the knee. Synvisc and Durolane are trade names for hyaluronic acid.

A recent study [3] compared the effect of PRP with hyaluronic acid. It showed that six months after treatment, the effect was similar, but favoured PRP. Twelve months after treatment, PRP had improved functional outcome scores compared to hyaluronic acid (graph below). This suggests that the treatment effect of PRP is more prolonged than hyaluronic acid. However, another well-designed study has shown no superiority of PRP [4].

Can you walk after PRP injection into the knee?

There are no restrictions on weight bearing after a PRP injections into the knee. Although you may have some minor discomfort immediately after the procedure, this should not impact on your ability to walk.

How fast does PRP work?

The effects of a PRP injection are not immediate. You will notice a slow improvement in the weeks and months after the PRP injection.

What are the side effects of a PRP injection into the knee?

The risks of a PRP injection are small but include infection, localised pain, an allergic reaction to the PRP serum (rare) and localised blood clots (rare).

Who is likely to benefit from PRP?

Patients with early arthritis without other structural problems within the knee (e.g. large unstable meniscal tears) may benefit from PRP injections to help with the pain. In advanced arthritis (bone-on-bone), PRP is unlikely to provide as much benefit as the damage in the joint is too advanced.

There are other non-surgical options for the management of osteoarthritis that are likely to be more effective and have more evidence behind them. These include weight loss, physiotherapy and anti-inflammatory medication. They should be tried as first line measures before considering PRP injections.

It’s important to get an assessment by a knee specialist before embarking on PRP therapy to see if it is a suitable option in your situation. PRP injections do not have a Medicare rebate and are usually provided with an out-of-pocket cost to patients (exceptions apply). If the arthritis within the knee is too advanced, surgery may provide much better relief of your pain.

Summary:

PRP can be effective in relieving pain and function in patients with early osteoarthritis by decreasing the inflammation in the knee and by promoting restoration of damaged cartilage. If PRP treatment is being administered, three consecutive PRP injections spaced two weeks apart gives the best results. It is important to note that it has a minimal benefit in advanced arthritis of the knee.

References

1. Görmeli G, Görmeli CA, Ataoglu B, Çolak C, Aslantürk O, Ertem K. Multiple PRP injections are more effective than single injections and hyaluronic acid in knees with early osteoarthritis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25(3):958-965. doi:10.1007/s00167-015-3705-6 ↩

2. Shen, L., Yuan, T., Chen, S. et al. The temporal effect of platelet-rich plasma on pain and physical function in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Orthop Surg Res 12, 16 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-017-0521-3 ↩

3. Dai WL, Zhou AG, Zhang H, Zhang J. Efficacy of Platelet-Rich Plasma in the Treatment of Knee Osteoarthritis: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Arthroscopy. 2017;33(3):659-670.e1. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2016.09.024 ↩

4. Di Martino, A., Di Matteo, B., Papio, T., Tentoni, F., Selleri, F., Cenacchi, A., Filardo, G. (2019). Platelet-Rich Plasma Versus Hyaluronic Acid Injections for the Treatment of Knee Osteoarthritis: Results at 5 Years of a Double-Blind, Randomized Controlled Trial. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 47(2), 347–354. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546518814532 ↩

Görmeli G, Görmeli CA, Ataoglu B, Çolak C, Aslantürk O, Ertem K. Multiple PRP injections are more effective than single injections and hyaluronic acid in knees with early osteoarthritis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25(3):958-965. doi:10.1007/s00167-015-3705-6 ↩

Shen, L., Yuan, T., Chen, S. et al. The temporal effect of platelet-rich plasma on pain and physical function in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Orthop Surg Res 12, 16 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-017-0521-3 ↩

Dai WL, Zhou AG, Zhang H, Zhang J. Efficacy of Platelet-Rich Plasma in the Treatment of Knee Osteoarthritis: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Arthroscopy. 2017;33(3):659-670.e1. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2016.09.024 ↩

Di Martino, A., Di Matteo, B., Papio, T., Tentoni, F., Selleri, F., Cenacchi, A., Filardo, G. (2019). Platelet-Rich Plasma Versus Hyaluronic Acid Injections for the Treatment of Knee Osteoarthritis: Results at 5 Years of a Double-Blind, Randomized Controlled Trial. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 47(2), 347–354. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546518814532 ↩